Email: geoff@geoffdann.co.uk

16/03/2018

Jew’s Ear (Auricularia auricula-judae) fruiting from an old Elder tree, in a cemetery, in winter.

There’s a lot of Jew’s Ears (Auricularia auricula-judae) around at the moment – it is one of the few edible wild fungi that can be found right through the year, and it is typically abundant throughout the winter. And that means there’s a lot of something else around at the moment: arguments on the internet about the acceptability of its name, some of which escalate into extremely bad-tempered personalised battles. The truth, as usual, tends to get lost in the crossfire.

This battle, in its modern British form, originates with a decision first by Plant Life International in 2003, and then by the British Mycological Society (the “BMS”) in 2005, to give it a new official name of “Jelly Ear”. In recent years the BMS has embarked on a project to designate official English common names for fungi, with the stated goals of making fungi more accessible (and fun) to non-scientists (by reducing the need to use cumbersome Latin names) as well as avoiding confusion where a species has more than one common name, or a common name refers to more than one species. All well and good, but this example doesn’t fit into either of those categories: “Jew’s Ear” (or names it is derived from) has long been the recognised common name for this species (it is the oldest English common name for any fungus), and it only refers to this species. This is the sole case where a decision was made to replace an established common name with a newly invented one, and the motivation was political. While the BMS has no legitimate authority to impose political judgements on the English-speaking world, it nevertheless had to make a decision as to what the “official” common name of this species was to be, and since accusations of anti-semitism were already rife on the other side of the Atlantic, the BMS played it safe and adopted a new name. I think this was the wrong call, and this post explains why.

Hottentot Fig (Carpobrotus edulis).

Why is this name considered, by some, to be “anti-semitic”? Usually no justification is given – people condemning the name seem to just expect everybody else to assume it is self-evidently anti-semitic. But plenty of species have similar common names that aren’t considered derogatory. Are we going to reject the names “Lady’s Slipper” (Cypripedium reginae) or “Lady’s Smock” (Cardamine pratensis) for being sexist? Are “Monk’s Rhubarb” (Rumex spp.) or Star-of-Bethlehem (Ornithogalum angustifolium) anti-Christian? What about Hottentot Fig (Carpobrotus edulis)? This is an edible plant native to south Africa, but well established in Europe. “Hottentot” is an old Dutch name for a southern African tribal people now more correctly known as “Khoekhoe”, and the etymology suggests “stutterer”, or just an approximation of what Khoekhoe language sounds like to dismissive European ears. As such, it is polite today to refer to these people by the name they use for themselves and “Hottentot” is considered mildly derogatory, but I’m yet to hear anybody suggest we rename Carpobrotus edulis something boring and inoffensive like “Succulent-leaved Fig”. But “Jew’s Ear” doesn’t even reach this level of offensiveness – what is actually offensive or discriminatory about “Jew’s Ear”?

One theory that’s been postulated during these online battles is that the Nazis issued anti-semitic propaganda posters depicting Jews as “ugly” – with over-sized ears and noses. This may well be true, but since the name of the fungus predates the Third Reich by several centuries, the claim of a causal connection with Nazi propaganda doesn’t make sense. The accusation of anti-semitism also predates the Nazis, the first example anyone can find coming from American mycologist Curtis Gates Lloyd (1859-1926). But Lloyd’s main claim to fame was his eccentric opinions on fungal naming conventions (in both Latin and English), and I can find no account of his justification for rejecting this one – just another claim that it is a self-evident “slander on the Jews”. He also disliked the Latin version (which means exactly the same thing) for being too long and including a convention-busting hyphen.

And it is in America that the modern rejection of the name on spurious grounds began. Here, for example, is an article that appeared in the summer 2005 edition of the Long Island Mycological Club’s newsletter. It contains several pages of hysterical wailing about the anti-semitic nature of the name “Jew’s Ear”, but is notably lacking in supporting evidence. First it claims that “Nazi hate literature” published in 1938 made some connection between this fungus and anti-semitism, but beyond the wild, vague accusations, there is neither any detail nor any link or reference to the material in question. And anyway, since the article itself acknowledges that the name predates the Nazis by several centuries, why does anything they wrote about it matter? The author then goes on to claim that “the most likely origin of the name is the hysterical anti-semitism that burgeoned in the middle-ages…” No actual reason is given for why it is “most likely”. The most interesting thing about this article is the way it portrays America, with its powerful Jewish lobby, as blazing the way forwards on this matter (even changing the Latin name to Auricularia auricula) while the UK and the rest of the “old world” are still backwardly wallowing in the middle ages. Thus it seems the BMS decision was influenced by a culture of anti-anti-semitic witch-hunting in the United States.

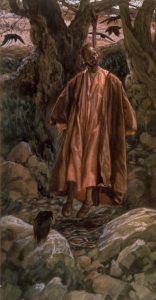

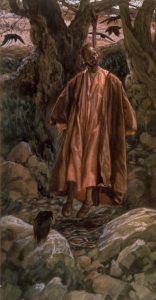

Judas Iscariot hanging from a tree (which looks a bit large and robust to be Elder…)

The origin of this name is not a mystery, and does not appear to have much to do with anti-semitism or Judaism. The name was originally “Judas’s Ear”. The Latin specific epithet “auricula-judae” means “Judas’s Ear”. This name was derived from a Christian myth that Judas Iscariot hung himself from an Elder tree, and because Jew’s Ears particularly like to grow on Elder, it was said that Judas’s spirit passed into the tree, and thus these fungi are somehow his ears.

From the American article: “Why, then, is this fungus also known as “Jew’s Ear”? How and when did “Judas’s Ear” become “Jew’s Ear”? Or did these variant names exist together all along simply because Judas was associated with the Jews?”

The answer is simple: it is a contraction. – “Judas’s Ear” became “Judas Ear” or “Jude’s Ear”, which was eventually shortened to “Jew’s Ear”. No anti-semitism – just the English language evolving to leave a consonant out here or there. The fact that the author of the article is absolutely convinced that this must have been the deliberate work of people who hated Jews is of no relevance.

The article continues: “We will probably never know the precise answers to these questions…” and “. I believe there was no mistranslation…” Lots of “probably”, “we don’t know” and “I believe.” But no evidence.

The Elder mythology is itself something of a curiosity. An older traditional claim is that Judas hung himself on a Mediterranean Redbud tree (Cercis silquastrum). And anyone familiar with Elder must surely agree that it is a strange choice of tree to hang yourself from: it’s just not robust enough, and you’d expect the branches to break. Although Elder does occur in the Levant, there is no historical record of an association with Christianity until that religion started to exert its authority in Europe, and this is where we need to look to discover the true origin of these myths.

Two Christian myths appeared in medieval times regarding Elder. One was that Elder wood was used to make the cross Jesus was crucified on (again, a very strange choice from a practical point of view), and the other was this story about Judas hanging himself. Both myths associate Elder with bad things. But there was already a rich Pagan mythology surrounding Elder in which it was associated with feminine spirituality (see here and here). All across northern Europe, Elder was associated with Goddesses or “the Elder Mother”. The spirits of dead witches were said to inhabit Elder, and for these reasons the wood should only be burned with great caution and reverence. If you delve into the mythology and history of this era, the true origins of the Christian Elder mythology become clear: this was an attempt by the Catholic Church to displace Pagan beliefs that were profoundly incompatible with Christian theology with Christian mythology aimed at demonising the revered Elder tree and exorcising its feminine spirituality. And it largely worked.

So the truth is that there is no reason to believe that name “Jew’s Ear” is even remotely anti-semitic. If anything, it is anti-pagan. And in fact you’ll find that most Jews themselves don’t find the name offensive. Like so much political correctness, more people seem to be vicariously offended on behalf of other people, than people being offended themselves.

I am going to make a political statement myself: political correctness has become the scourge of modern western culture and is an obstacle to free thinking, free speech and the pursuit of truth. I am very much hoping that the election to the highest political office in the world of a person who pays no heed whatsoever to political correctness will be seen as a turning point. Perhaps, at long last, we have passed “Peak Political Correctness”. Another sign of this cultural change is the meteoric rise to fame of Canadian academic Jordan Peterson, whose interviews and youtube videos are inspiring a whole generation of younger people to abandon political correctness wholesale. The trigger for that rise to fame, along with the publication of his second book, was to point blank refuse to accept that the Canadian government had any right to compel him to use gender-neutral pronouns to when referring to transgender people: he viewed it as an assault on his freedom of expression, just as is the attempt to compel people to abandon the traditional name of A. auricula-judae.

Apart from anything else, the attempt to change the name of this fungus has failed. It was a case, perhaps, of it being better to let sleeping dogs lie. By attempting to impose a political directive, via language policing, the people who made this decision, rather than putting this issue to bed, have ensured that every time anybody uses either common name, this whole argument will re-ignite. And I am willing to bet that the traditional name will survive into the 22nd century and beyond, and the name “Jelly Ear” will forever be associated with a period in the late 20th and early 21st centuries when political correctness was allowed to steamroller the truth.

Apart from anything else, the attempt to change the name of this fungus has failed. It was a case, perhaps, of it being better to let sleeping dogs lie. By attempting to impose a political directive, via language policing, the people who made this decision, rather than putting this issue to bed, have ensured that every time anybody uses either common name, this whole argument will re-ignite. And I am willing to bet that the traditional name will survive into the 22nd century and beyond, and the name “Jelly Ear” will forever be associated with a period in the late 20th and early 21st centuries when political correctness was allowed to steamroller the truth.

Perhaps a compromise is available though. If “Jew’s Ear” is a contraction of “Judas’ Ear”, maybe we can make crystal clear that the name isn’t anti-semitic by reverting to the original, unshortened version, rather than imposing the bland, empty, boring, sanitised “Jelly Ear”.